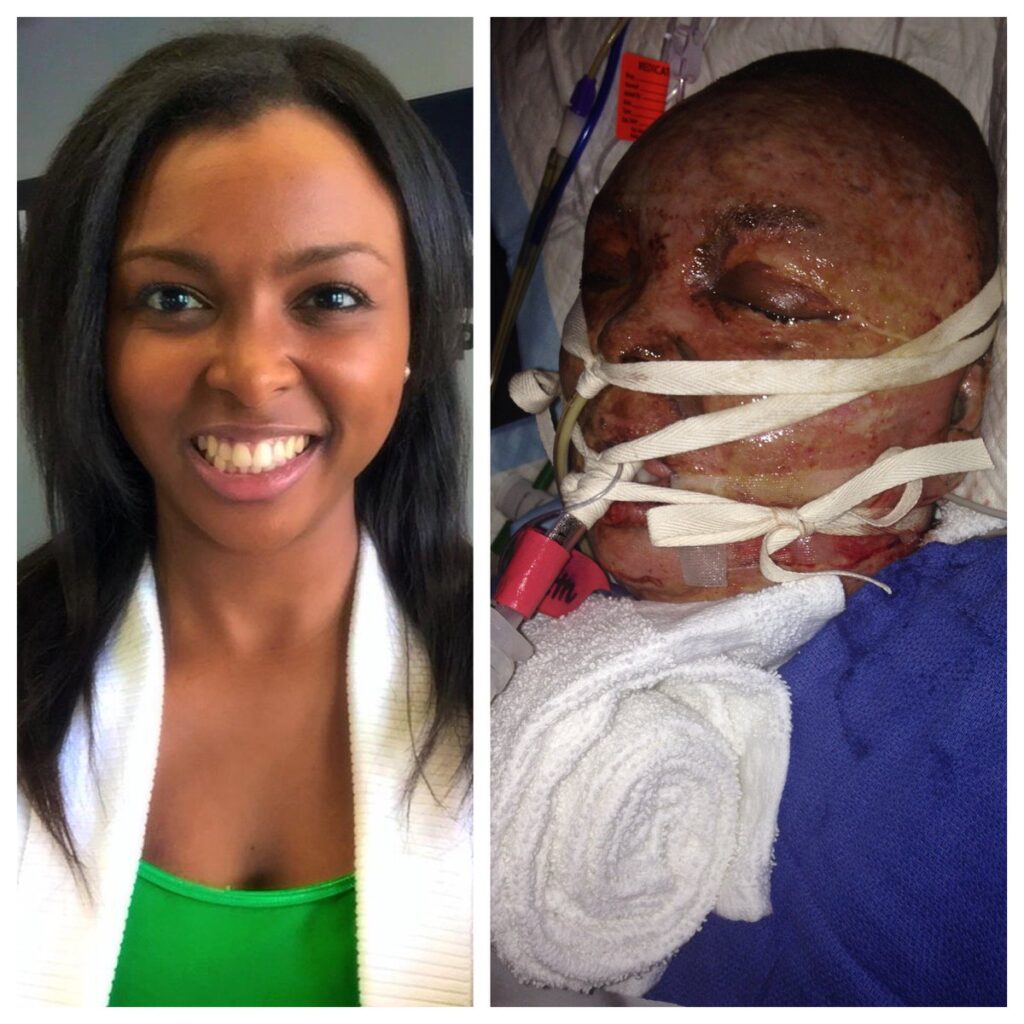

Scars cover every inch of my body. Eighty-five percent of them are from burns. There are also areas like my feet, which are part of the ‘other 15 percent.’ Still, skin was removed from those areas to help cover my body in skin grafts.

Those are just the scars you can see. Emotionally, I have been collecting scars since childhood. For the most part, those have been a lot less visible. As such, they were easier for everyone else — including myself — to ignore or push aside.

Twice I have been sexually assaulted: First by someone who was supposed to be family, then at the hands of a coach who is supposed to be a leader of young men. Growing up, I was raised to be ‘strong’ in a disaster — to smile and act like everything was great, even when that was the furthest thing from the truth. We weren’t a family that showed affection, or spent much time together.

Volleyball was my outlet. If I was frustrated, I would train or try to find a pick-up game. Of all life experiences and physical traumas I failed to deal with or acknowledge, the one that hit me the hardest was my controversial resignation from my job as the Florida State football beat reporter for the Tallahassee Democrat.

Journalism — much like volleyball when I was younger — was my sanctuary. When I couldn’t, didn’t want to, or didn’t know how to deal with something in my life, I turned to my work. Maybe I didn’t know how to be in a relationship or deal with trauma, but I knew how to talk to people, write a lede and structure a story. If nothing else, I knew — I just knew — I would always have that.

That feeling of certainty disappeared as I moved from Tallahassee, Florida to Birmingham, Alabama to work as college football reporter at AL.com. Suddenly, I had to adjust how I defined myself. ‘Journalist’ was no longer enough. Shortly after starting work in Alabama, I reunited with my first love, Chasten. Our reunion came after seven years of living very different lives. I had gone to college, earned my bachelor’s and master’s degrees and spent four years covering big-time college football. Meanwhile, he had spent most of his time in prison.

It was not a logical decision. It was one fueled by a desire for more, since I now knew I needed to find purpose in something besides storytelling. When I was in high school, Chasten offered me space to be vulnerable. To others, I was newspaper Natalie, volleyball Natalie, tough Natalie or Natalie with the jokes. To him, I was just Natalie. He made it easy for me to open up and show my emotional scars.

Still, as the product of a disastrous and abusive relationship, I refused to be his — or anyone else’s — ‘girlfriend.’ Even with the walls I had become a master at erecting, I couldn’t help it. I fell for Chasten. In our initial conversations after our reunion, he vowed that he had learned from his bad decisions and was ready to be a better man. I wasn’t one to fall for most people’s crap. But Chasten wasn’t most people to me. After a few weeks of talking on the phone, it felt like old times. But this time, we were older and he wanted a commitment from me. So, he moved to Alabama to be with me.

Not long after he moved in with me, he questioned how committed I was to him. Having felt somewhat guilty for cutting him off when I went to college, and not being there for him when he was making one poor decision after another, I wanted to prove that I was going to be there for him this time around. So, we got engaged. When that wasn’t enough, we took a detour on the way to the gym one day and ended up at the courthouse. We walked out of the courthouse, in our gym clothes, and married to each other.

The thing about him knowing me better than anyone else when I was 16 years old, was still true when I was 25. The problem was, he knew that questioning my commitment to something I was clearly committed to would frustrate me and make me want to further prove my commitment. After we got married, my hope was that he would find comfort and security in the vows we took. Instead, things – predictably – got worse. When I wasn’t working from home, he insisted on coming with me to the newsroom and on work trips.

He didn’t want me with male coaches, athletes or colleagues without his supervision. When we would go out with friends, I would get yelled at for

the rest of the night if a man smiled at me and I didn’t immediately go up to him tell him to stop, while acknowledging my husband. If he saw I had recently spoken to a male colleague on the phone, he would call the number, put it on speaker phone and tell me to prove that I wasn’t cheating with them. On the rare occasion when we weren’t together, he would regularly blow up my phone telling me what an awful wife and person I was.

Most of the time, being around him made me angry. I felt frustrated, smothered and trapped in a mess of my own making. But more than anything, I felt like I was on an island. He managed to alienate me from my sister, Jeanette, because she was a voice of reason whenever I mentioned our relationship. So, he would find ways to manufacture fights between us. Eventually, we stopped fighting…or talking at all. With some of my other friends, he would befriend them. Every once in awhile he would call one of them to say he was concerned with how much I worked or my anger towards him. The way he treated me made some of my other friends so uncomfortable that they increasingly came around less.

In the early hours of my 26th birthday, we fought about my travel schedule for the upcoming football season. He told me, if I went to all those games, he was going to leave me, take everything I had, and do whatever he had to do to make sure I no longer had a job to go to. It was a variation of the same fight we had almost daily. But this one was particularly bad. That morning, during the car ride home, he kept telling me how I had made a huge mistake in choosing my career over my marriage. As I turned into our complex, he lunged at me. I wasn’t sure what he was going to do, so I ran off the road into a tree as a distraction. After I hit the tree, he got out of the car and walked to our apartment. I just sat there looking at my Jetta and looking at the tree I hit. I had no idea how I was going to explain any of this to anyone. I just knew there was no way in hell I could go home that night.

There was a half-bottle of vodka in the backseat left over from what was supposed to be a relaxing day at the pool. I grabbed the bottle, opened it and quickly downed it. As I sat there, I thought about how things continued to get worse. At the time, I couldn’t imagine what worse would have even looked like. I popped the trunk and grabbed a bottle of almost-gone wine-slugging it down like it was Gatorade and I had just finished a marathon. I was pretty sure that I had officially hit rock bottom.